By Bill Griffith

PORTLAND, CT—You know him as “Roger,” the sometimes funny, sometimes curmudgeonly (and often both) 82-year-old ace mechanic on Velocity’s “Chasing Classic Cars.”

He plays off show centerpiece Wayne Carini so well that you are immediately drawn into the nitty, gritty of the mechanical fixes. How well? So well that Roger rates an Emmy as Best

Supporting Character in a continuing series.

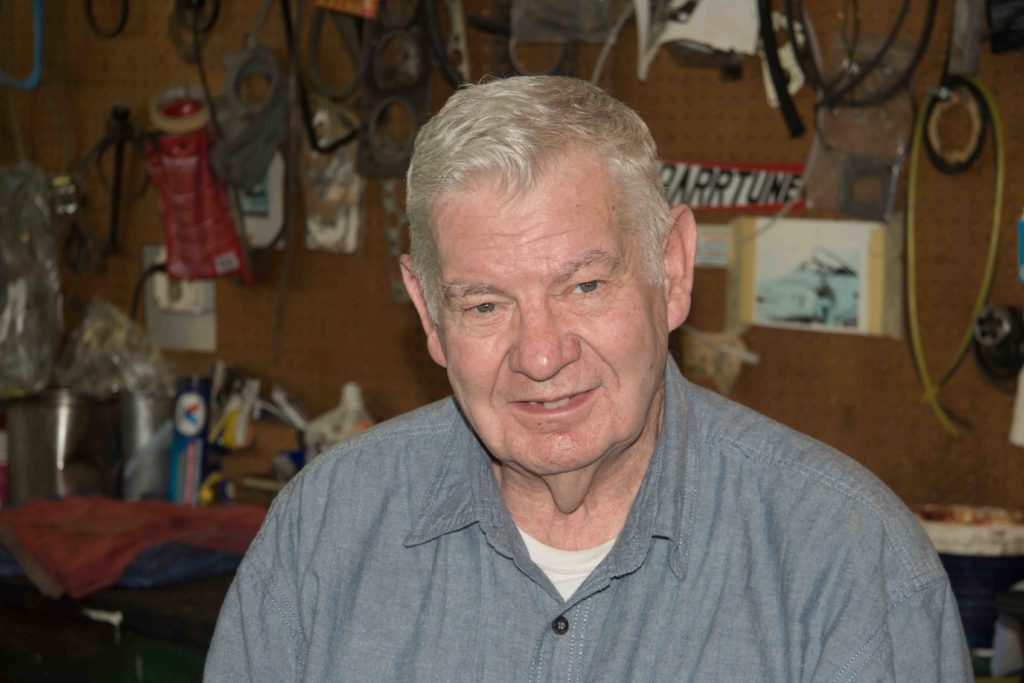

Roger Barr, ace mechanic on Velocity’s “Chasing Classic Cars”

What’s a normal daily scene at Carini’s F40 Motor Sports is the stuff that makes the TV series, in its 13th season, an enduring part of auto enthusiasts’ viewing.

Take the day the state of New York sent FDR’s 1932 Packard Phaeton to Carini to get it back in running order. The catch: It had to be done in 12 days so Governor Andrew Cuomo could drive

the Packard across the new Tappan Zee Bridge, officially opening the span.

For starters, Wayne gives Roger E. Barr the Packard job with instructions to start by rebuilding the carburetor and getting some oil into the cylinder heads.

Naturally, the job gets done on time and the car rolls across the bridge, named after Cuomo’s father, back in operating shape and on new tires.

Later, the New York media wonders why the job was: 1) Sent out of state and 2) Cost $10,439.

There’s no question why Carini was chosen. His work (and his dad’s) has spoken for itself for decades.

Meanwhile, the cost was of interest to fans of the show who often wonder about the rarely revealed Carini finances—how much he pays for cars, how much it costs to restore them, and what he makes on their sales. On the other hand, it’s exactly that confidentiality that keeps the rich, the famous, and the common man contacting Carini.

It’s happened multiple times. These days, in addition to chasing the cars, the cars chase Carini.

A car collector will pass away. Among his (or her) papers is a note to contact Wayne and ask him to buy, sell, or take the vehicles to auction.

“Sometimes these are people I’ve never met,” says Carini.

A few of those vehicles make their way into his extensive private collection, others are sold from F40 or go to auction.

Roger Barr often has two hands—and some commentary involved in the process—a blessing to viewers because he’s recently recovered from an infected leg that cost him extended time from work.

If he has one gripe, it’s that he goes from one job to another on the many “works in progress” at F40’s sprawling operation. “I’m 82. If I start on a car, I’d like to see it run in my lifetime,” he grumps.

Of course, he’s seen most all of these vehicles running in their primes.

He grew up on Staten Island. At age 4 or 5, he started hanging around at Joe’s neighborhood garage. “My mother would cry every day when I came home covered in grease and oil,” he says.

“Any exotic car on the island went there. Auburns, Cords, Packards, and Dusenbergs. I loved to hear them coming and going.

“When Joe tuned a Packard V-12, he really would put a glass of water on top of the engine and agonize if there were any ripples to be seen.

“His was a one-light-bulb, no-heat shop, but he was a gifted guy. I remember he always had a White Owl cigar, but I’m not sure whether he smoked ‘em or chewed ‘em.”

When Roger was 6, his dad tired of his son’s constant questions on all topics and pointed to all the books in their house. “The answers are in there,” he told me.

“I have a major problem with dyslexia,” says Roger, “but I learned to read. However, I can’t spell.”

When he told his parents that he wanted to be an aviation mechanic, his dad moved the family to New Jersey, near the top-rated Paterson Tech. The catch was Roger had to come up with the $450 tuition.

“I did a lot of jobs,” he says, “but babysitting at 75 cents and hour was the best.”

Roger graduated in 1953 with his A&E license, followed shortly by greetings from Uncle Sam during the Korean conflict.

“In my senior year, my aviation tech teacher got me on the list to go to Teeterboro Airport for five days, four hours a day so I’d qualify for that license,” he says. “It meant I was able to fix airplanes instead of just gassing them up and servicing them.”

“Without that license, I’d have been a soldier in Korea,” he says. “Instead, they welcomed me as an aircraft mechanic and asked where I’d like to be stationed. I looked at the map and picked Germany, about as far from Korea as I could get.”

There he worked on planes and got an introduction to sports car racing, serving as a backup driver for big-time club racing teams, an invitation he earned by racing MGs competitively against faster Porsches.

In those enduro races, when a top driver broke down, he jumped into a backup car.

“It was the driver, not the car, who won the race,” says Roger. “So I’d have to get out of my car, often out on the track. I had to walk back [to the pits] at most every track in Europe.

“If you want to learn to drive well, you’ve got to get into the European mindset. You have to start with no power and learn to make that car go fast.”

Still, he had hot rod props in his past, having built a ’34 Ford with an Olds V-8, but sports car racing was more his thing, and he raced MG TDs and MGAs on road courses.

He brought that racing knowledge and a talent for inventing “tricks of the trade” home with him and went to work at Pratt & Whitney, got into Formula Vee and Formula B racing, teaching engineering, operating his own shop, and, in “retirement” has been working at F40 for a dozen years.

At Pratt & Whitney, located on the site where Rentschler Field is today in East Hartford, he worked on testing jet engines to survive bird strikes.

“Animal lovers wouldn’t like it, but we trapped seagulls in a rocket net, then fired them out of a cannon into the engines,” says Roger. “High speed cameras would show the bulge where they destroyed the engines.”

It led to the engineering solution to make the blades flexible enough to survive, but it wasn’t pleasant.

“This was in the summer time. Seagull guts in the heat left a terrible stench,” he says.

So did trapping them.

“Gulls defend themselves by defecating on their wings and slinging it at you,” he says.

All-in-all, it turned out that working on Gullwing coupes was preferable.

But it started more modestly with office workers asking him to fix their cars.

That led to owning The Foreign Car Shop in Glastonbury, CT.

“I managed to lose money, but at least I owned the building,” he says. That he eventually sold to Gene Langan Volkswagen dealership.

Later, he’d teach for a decade at Brown and another five years at the University of Hartford, guiding engineering students in Formula SAE national car-building competition. The program, started by the Society of Automotive Engineers, tests teams’ abilities in eight areas.

“You’ve got to design the vehicle, do a cost and manufacturing analysis, make a presentation (think Shark Tank), then test it for acceleration, fuel economy, endurance, handling (skidpad and slalom),” he says.

“The students who really got into it, couldn’t get enough [of the project],” says Roger. “Those were the kids who went on to get outstanding jobs.”

After graduation, they took with them Roger’s tricks for going fast, cutting weight, and thinking the way he did in finding ways to make his Formula Vee go fast enough to win a pair of Northeast championships.

The class, designed to make racing competition even and affordable, “is a tinker’s paradise,” says Roger.

He invented the “kluge,” a simple-but-true swing axle adaption that went from side to side, using a cable-and-pulley with a hidden spring from a 1961 Mercedes-Benz hood hidden in a piece of tubing. He also came up with ways to maximize fuel flow through the intake manifold (“The right manifold is worth $5,000”), machining a paper-thin venturi, finding the smallest possible ’60 Bug wheels and slightly modifying flywheels that still met the 12-pound requirement.

As for modern technology?

“The old-timers had the same knowledge,” he says. “The difference today is metallurgy with better and thinner alloys, stuff that couldn’t be done on a mass scale in the past.”

He remembers the first Ferrari V-12 he assembled.

“A guy sent it to us in boxes and packages. It ran pretty good when it was done.”

With a straight face, he says, “What I do isn’t difficult.”

Great article about a fascinating individual loved and respected by car enthusiasts. Roger is the reason I enjoyed “Chasing Classic Cars”. I wish him the best.